Fashion modeling is the art and profession of displaying clothing, accessories, and beauty products to inspire consumer desire and communicate a designer’s vision. More than simply wearing garments, models embody the aesthetic, attitude, and cultural moment that fashion seeks to capture. They serve as living canvases where textile becomes narrative, transforming fabric into aspiration.

Modeling became essential to the fashion modeling industry as commerce and artistry converged in the nineteenth century. When fashion houses needed to showcase their creations beyond static illustrations, they turned to human forms that could bring movement, personality, and relatability to their designs. What began as a practical marketing tool evolved into a sophisticated art form that bridges commerce, culture, and visual storytelling.

Throughout history, fashion modeling has functioned as a mirror reflecting the social, cultural, and beauty standards of each era. The models chosen to represent fashion ideals reveal what societies value, fear, and aspire to become. From the corseted silhouettes of Victorian aristocracy to the diverse, inclusive runways of today, modeling captures the zeitgeist of its time, documenting shifts in gender roles, body politics, racial attitudes, and economic aspirations. Each era’s models don’t just wear the clothes—they embody the dreams and anxieties of their generation.

Early Origins of Fashion Modeling (Before the 1900s)

Long before human models graced runways, fashion was communicated through inanimate forms. Dressmakers and tailors employed mannequins, wooden dress forms, and elaborately clothed miniature dolls to showcase their designs. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, fashion dolls called “Pandoras” traveled between European courts, dressed in the latest styles from Paris. These twelve-to-eighteen-inch figures served as three-dimensional fashion plates, allowing aristocrats across the continent to view and order the newest trends without traveling to France themselves.

The role of royal courts and elite dressmakers was paramount in establishing fashion standards. Monarchs and their courtiers didn’t simply wear clothes—they made political and social statements through their attire. Dressmakers to royalty held positions of influence, and their creations set trends that cascaded through social hierarchies. Marie Antoinette’s dressmaker, Rose Bertin, became one of the first celebrity fashion designers, wielding considerable cultural power through her access to the queen’s wardrobe.

Paris emerged as the undisputed center of fashion by the eighteenth century, a position it would maintain for generations. The city’s concentration of skilled artisans, wealthy clientele, and cultural prestige created an ecosystem where fashion could flourish as both art and industry. French dressmakers developed sophisticated construction techniques and established the haute couture tradition that would later require living models to fully appreciate.

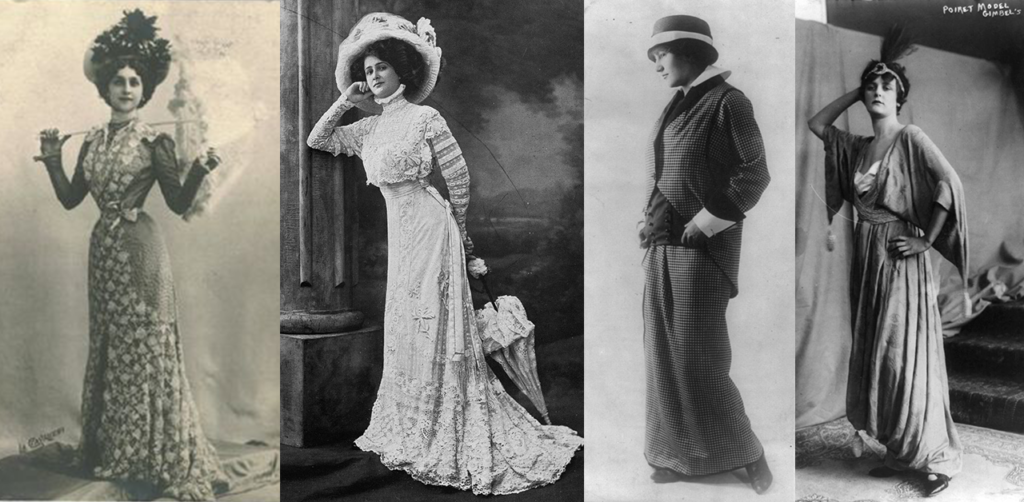

The first known live models appeared in Parisian couture houses in the mid-nineteenth century. These women, often called “sosies” or house models, would try on garments for clients, allowing potential buyers to see how designs looked in motion on human forms. This practice represented a radical shift from static display, introducing personality, movement, and the subtle art of presentation that would define modeling for generations to come.

The Birth of Professional Fashion Models (Late 1800s – Early 1900s)

Charles Frederick Worth, the father of haute couture, revolutionized fashion presentation in the 1850s and 1860s by employing his wife, Marie Vernet Worth, as the first professional fashion model. Marie would wear his creations at social events and in his Paris salon, demonstrating how the garments moved and draped on a living person. This innovation transformed fashion from a made-to-order craft into a creative industry where designers could present collections and establish brand identity.

Worth’s salon shows established the template for modern fashion presentation. Rather than simply fitting clients for custom garments, he invited them to view seasonal collections modeled by young women employed specifically for this purpose. These private presentations for elite clientele represented the earliest form of fashion shows, combining theater, commerce, and social ritual. The models glided through ornate salons, pausing to display details and turn to reveal the construction of each piece.

This shift elevated modeling from an informal practice to a respectable profession for women, though it remained controversial. In an era when working-class women had limited career options and middle-class women were expected to avoid public display, fashion modeling occupied an ambiguous social space. House models in prestigious establishments enjoyed better working conditions and higher status than most working women, yet they still faced scrutiny for making their appearance a commodity. The profession attracted women seeking independence and willing to navigate the complex social boundaries of late Victorian society.

Early beauty ideals and body standards for models emphasized a specific aesthetic that reflected contemporary tastes. The ideal fashion model of the late 1800s and early 1900s possessed an hourglass figure, achieved through corseting, with a full bust, narrow waist, and rounded hips. She stood between five feet six inches and five feet eight inches tall—statuesque for the era—with pale skin, delicate features, and an air of refined elegance. These standards reflected both the clothes they modeled, which required specific proportions, and the class-based beauty ideals of wealthy European and American society.

Fashion Modeling in the 1920s–1930s: The Rise of Modern Fashion

The 1920s brought seismic social changes that revolutionized fashion modeling. Women’s liberation movements, suffrage victories, and the cultural upheaval following World War I created space for new expressions of femininity. The flapper era rejected Victorian constraints, both literally and figuratively. Models embodied this shift, abandoning corsets for drop-waist dresses, cutting their hair into bobs, and projecting an attitude of independence and modernity. The ideal silhouette became straight and boyish, emphasizing youth, mobility, and freedom rather than maternal curves.

Fashion magazines exploded in popularity during this period, creating unprecedented demand for print models. Publications like Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Vanity Fair became arbiters of style, reaching middle-class readers who aspired to the fashions once reserved for the wealthy. These magazines required countless photographs and illustrations, providing regular employment for models and establishing them as recognizable figures rather than anonymous mannequins. Readers began following favorite models, learning their names, and associating them with particular styles or designers.

Editorial fashion photography emerged as an art form distinct from commercial documentation. Pioneering photographers like Edward Steichen, Baron Adolf de Meyer, and George Hoyningen-Huene treated fashion photography as creative expression, experimenting with lighting, composition, and atmosphere. Models became collaborators in this artistic process, learning to convey mood and narrative through pose and expression. The relationship between photographer, model, and designer created a new visual language that defined modern fashion imagery.

The Great Depression presented significant challenges for the fashion industry and modeling profession. As economic hardship spread, luxury fashion contracted sharply. Many couture houses closed or scaled back operations, and modeling opportunities dwindled. However, the crisis also democratized fashion in certain ways. Ready-to-wear clothing expanded, creating new markets for catalog and commercial modeling. Hollywood also emerged as a fashion influence during this period, with film stars becoming style icons and some studios employing models for costume departments. The resilience of modeling through economic catastrophe demonstrated the profession’s essential role in selling aspiration even during hardship.

The Golden Age of Fashion Modeling (1940s–1950s)

The post-war fashion boom of the late 1940s and 1950s represented a golden age for haute couture and fashion modeling. After years of wartime austerity and rationing, Christian Dior’s 1947 “New Look” collection sparked a renaissance of luxury fashion. The return to feminine, sculptured silhouettes with nipped waists and full skirts required skilled models who could showcase the architectural precision of these garments. Fashion houses in Paris, New York, and other fashion capitals expanded dramatically, employing larger stables of house models and staging increasingly elaborate presentations.

Iconic fashion photographers emerged as creative forces who shaped how the world saw fashion. Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, Horst P. Horst, and Cecil Beaton created images that transcended commercial photography, entering the realm of fine art. These photographers developed distinctive visual signatures and often maintained long-term collaborations with specific models. Their work appeared in magazines but also in galleries and museums, elevating both photography and modeling to cultural legitimacy.

Models began emerging from anonymity to become recognized muses and personalities. Lisa Fonssagrives, often considered the first supermodel, appeared on over 200 Vogue covers and worked with every major photographer of her era. Dovima, Jean Patchett, Dorian Leigh, and Suzy Parker became household names, their faces synonymous with elegance and sophistication. These women were no longer interchangeable mannequins but individuals whose unique qualities contributed to the fashion narrative. Designers and photographers chose models not just for their measurements but for their distinctive presence and ability to embody a particular vision.

Haute couture reached its zenith during this period, supported by luxury branding and an international clientele of wealthy women who traveled to Paris twice yearly for seasonal collections. The major couture houses—Dior, Balenciaga, Givenchy, Chanel—employed teams of models for their salon shows, which became increasingly theatrical and exclusive. These presentations combined fashion, performance, and social ritual, with models trained to move with precise choreography through elegant salons. The relationship between haute couture and modeling was symbiotic: couture needed models to bring designs to life, while models gained prestige and higher fees from association with prestigious houses.

The Supermodel Era (1960s–1990s)

1 1960s–1970s: Youth Culture & Diversity Begins

The 1960s shattered previous modeling conventions with Twiggy’s arrival. The sixteen-year-old British model possessed an androgynous, almost childlike appearance that contrasted sharply with the sophisticated elegance of 1950s models. Standing just five feet six inches and weighing barely 90 pounds, Twiggy personified the youthquake that transformed fashion. Her short haircut, emphasized eyes, and extraordinarily slim frame established an aesthetic that prioritized youth, innocence, and a departure from maternal femininity. This shift had complex implications, opening doors for younger, less conventional looking models while establishing extreme thinness as the industry standard.

Cultural revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s disrupted established beauty hierarchies and introduced new ideals. The counterculture movement, civil rights activism, and feminist consciousness challenged monolithic beauty standards. Fashion began tentatively incorporating more diverse aesthetics, though progress was halting and incomplete. Designers like Yves Saint Laurent drew inspiration from global cultures, and models like Veruschka embodied a more exotic, bohemian aesthetic that reflected the era’s fascination with non-Western cultures.

International modeling expanded significantly during these decades. Models from Europe, especially Britain, Scandinavia, and Germany, joined their American counterparts on magazine covers and runways. The jet age made it feasible for models to work in multiple fashion capitals, and agencies began establishing international networks. Tokyo, Milan, and Sydney developed significant fashion industries with their own modeling communities. However, the global expansion of modeling initially meant the worldwide spread of Western, predominantly Caucasian beauty standards rather than genuine diversification.

The late 1960s and 1970s saw the first notable Black models achieving mainstream success, though they remained exceptions in a predominantly white industry. Donyale Luna became the first Black model on the cover of British Vogue in 1966. Beverly Johnson broke barriers as the first Black model on the cover of American Vogue in 1974, a milestone that revealed how thoroughly racial discrimination had defined fashion modeling. Iman, Pat Cleveland, and Bethann Hardison achieved success in the 1970s, but their presence highlighted rather than resolved the industry’s diversity deficit. These pioneering models faced extraordinary pressure as representatives of their race while navigating an industry that often tokenized or exoticized them.

1980s–1990s: The Supermodel Phenomenon

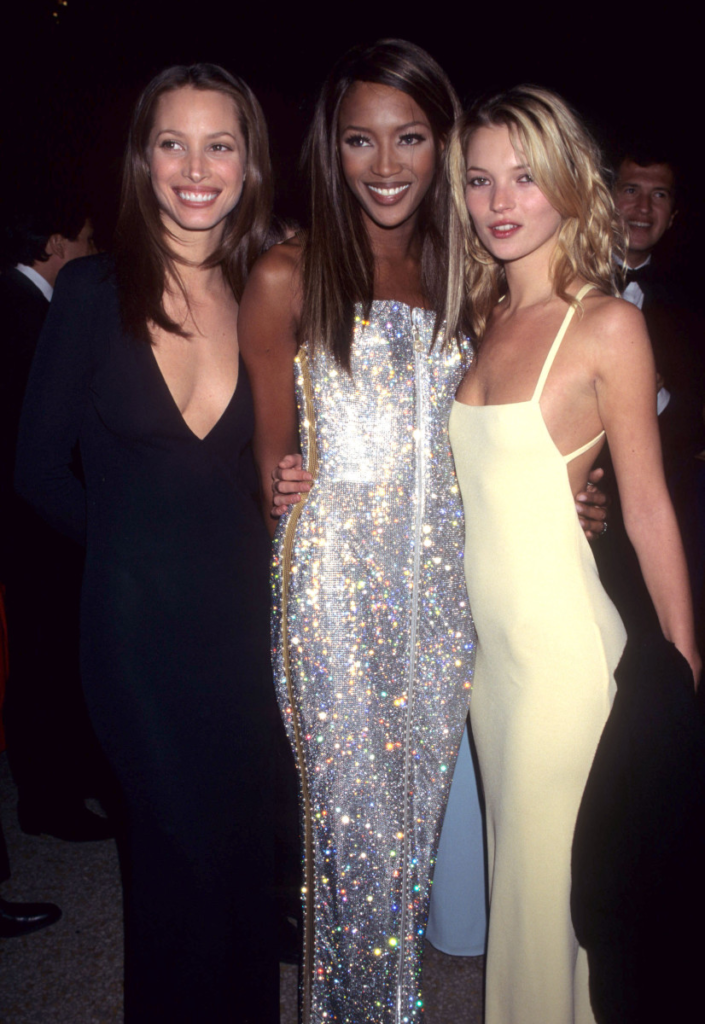

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed the supermodel phenomenon, where a select group of models achieved unprecedented celebrity status. Christy Turlington, Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Cindy Crawford, Claudia Schiffer, and Kate Moss became household names, recognized even by people with no interest in fashion. These women transcended their profession to become global celebrities, appearing on talk shows, in music videos, and on magazine covers devoted to their personal lives rather than the clothes they wore.

Supermodels wielded extraordinary power in the fashion industry, commanding fees that previous generations could barely imagine. Linda Evangelista famously declared she wouldn’t wake up for less than $10,000 a day, a statement that symbolized the supermodels’ leverage. Top models could make or break fashion shows with their presence, and designers competed to book them. This era marked the peak of model influence, when their names could sell magazines, fill runway show seats, and elevate brand prestige.

Runway dominance characterized the supermodel era. Major fashion shows became theatrical spectacles where supermodels were the stars. Designers choreographed their shows around these personalities, and the finale walk, where all supermodels appeared together, became an iconic moment of fashion presentation. Gianni Versace’s shows epitomized this approach, featuring supermodels in glamorous, body-conscious designs, often accompanied by rock music and exuberant energy. The runway became less about quietly displaying clothes and more about creating spectacular fashion entertainment.

Brand endorsements and commercial contracts multiplied for supermodels, establishing lucrative revenue streams beyond editorial and runway work. Cindy Crawford’s contract with Pepsi, Claudia Schiffer’s association with Chanel, and numerous other partnerships made supermodels wealthy and extended their reach beyond fashion audiences. These endorsements also shifted the economics of modeling, with commercial work often paying significantly more than high-fashion editorial or runway jobs, despite editorial maintaining higher prestige.

Media influence and pop culture crossover defined the supermodel phenomenon. These models appeared in George Michael’s “Freedom! ’90” music video, dated celebrities, and married rock stars and actors. They hosted television shows, acted in films, and became subjects of intense media scrutiny. This crossover meant that modeling became intertwined with entertainment, celebrity culture, and lifestyle branding. The supermodel was not just a clothes hanger but a complete personality whose lifestyle, relationships, and opinions became part of their marketable image.

Fashion Modeling in the 2000s: Globalization & Digital Media

The early 2000s witnessed a deliberate shift away from supermodel celebrity toward more anonymous, accessible-looking models. Designers and magazines began favoring what became called the “girl-next-door” aesthetic—models who appeared more relatable and less intimidating than the glamorous supermodels. This trend reflected changing marketing strategies that emphasized aspirational accessibility rather than untouchable luxury. Models like Gemma Ward and Lily Cole possessed distinctive, sometimes unconventional looks that suggested individuality rather than perfect beauty.

Fashion weeks proliferated globally during this period, moving beyond the traditional Big Four cities of New York, London, Milan, and Paris. Significant fashion weeks emerged in Tokyo, Shanghai, São Paulo, Sydney, Mumbai, and dozens of other cities. This geographic expansion created more opportunities for models while also regionalizing fashion modeling. Local models could build careers in their home markets, and international clients sought models from diverse backgrounds to appeal to global consumers.

Fast fashion brands like Zara, H&M, and Forever 21 experienced explosive growth, creating an entirely new sector of commercial modeling. Unlike luxury fashion’s emphasis on editorial prestige and runway glamour, fast fashion required massive quantities of catalog and e-commerce imagery for rapidly changing inventory. This commercial work provided steady employment for thousands of models but at lower rates and with less prestige than high-fashion work. The division between editorial/runway models and commercial models became more pronounced, with different career trajectories and aesthetic standards for each sector.

The early internet began impacting modeling careers, though its revolutionary effects wouldn’t fully manifest until the following decade. Modeling agencies established websites showcasing their talent, allowing clients worldwide to browse and book models remotely. Online modeling portfolios supplemented or replaced physical books, and casting directors could review hundreds of models without in-person meetings. Digital photography replaced film, making photo shoots faster and cheaper while allowing for immediate review and adjustment. These technological shifts increased efficiency but also intensified competition, as agencies could now recruit and manage models globally.

The Social Media Era of Modeling (2010s–Present)

Instagram, TikTok, and other social media platforms revolutionized fashion modeling by giving models direct access to audiences. Previously, models relied entirely on agencies, photographers, and publications to control their image and reach consumers. Social media disrupted this gatekeeping, allowing models to build personal brands, engage with fans, and demonstrate their value to potential clients through follower counts and engagement metrics. A model’s Instagram following became as important as their runway experience or editorial portfolio, fundamentally altering the criteria for booking decisions.

The rise of influencer models blurred the lines between traditional modeling and content creation. Young women (and increasingly men) built modeling careers entirely through social media, bypassing traditional pathways of agency scouting and editorial tear sheets. These influencer-models generated their own content, collaborated directly with brands, and monetized their following through sponsored posts, affiliate marketing, and personal merchandise. The most successful influencer-models like Kendall Jenner bridged both worlds, walking major runways while maintaining massive social media audiences.

Power dynamics between brands and models shifted dramatically in the social media era. Models with large followings possessed leverage independent of agency representation or editorial credibility. Brands increasingly booked models based on their ability to promote products to engaged audiences rather than purely on their look or prestige. This democratized aspects of modeling by creating opportunities outside traditional fashion industry gatekeepers, but it also intensified pressure on models to constantly create content, engage with followers, and build their personal brand alongside their modeling work.

Direct-to-brand collaborations became common as models with substantial followings could negotiate partnerships without agency intermediation. A model with millions of engaged followers could approach brands directly, propose collaborations, and negotiate terms based on their demonstrated ability to drive consumer engagement and sales. This disintermediation challenged the traditional agency model and created new revenue streams for models who successfully cultivated their online presence. The most entrepreneurial models launched their own brands, using their platform to sell clothing, beauty products, or lifestyle goods directly to their audience.

Diversity, Inclusion & Changing Beauty Standards

The push for size-inclusive, age-inclusive, and gender-fluid modeling gained momentum throughout the 2010s and into the present. Plus-size models like Ashley Graham, Tess Holliday, and Paloma Elsesser challenged the industry’s extreme thinness standards, appearing in mainstream fashion magazines and walking major runways. Age diversity expanded beyond the token inclusion of older women, with models over fifty and sixty appearing in campaigns that celebrated beauty across the lifespan. Gender-fluid and transgender models including Andreja Pejić, Hari Nef, and Hunter Schafer broke barriers in high fashion, appearing in campaigns for major luxury brands and walking runways previously restricted to cisgender models.

Representation across races and ethnicities improved significantly, though unevenly, during this period. The early 2010s saw renewed criticism of overwhelmingly white runways and editorial spreads, prompting some fashion houses and publications to increase diversity. Models of color achieved breakthrough success, with women like Adut Akech, Anok Yai, and Liu Wen becoming faces of major luxury brands. However, representation remained contentious, with critics pointing out that improvement often stalled at tokenism, diversity was unevenly distributed across fashion sectors, and models of color still faced discrimination in booking decisions, pay equity, and career advancement.

Models with disabilities began appearing in mainstream fashion during the 2010s, challenging deep-seated assumptions about beauty and ability. Models like Aaron Rose Philip, who uses a wheelchair, and Ellie Goldstein, who has Down syndrome, appeared in campaigns for major brands including Gucci and Cambio. Madeline Stuart walked at New York Fashion Week, and numerous models with limb differences, including Kelly Knox and Mama Cax, built successful careers. This representation remained limited but signaled expanding definitions of beauty and fashion’s potential to reflect human diversity more authentically.

Consumer demand increasingly shaped industry change toward greater inclusion. Social media empowered consumers to criticize brands for lack of diversity, size exclusion, or outdated beauty standards, often generating viral backlash that affected brand reputation and sales. Younger consumers particularly expected brands to reflect diverse beauty ideals and penalized those perceived as exclusionary. This market pressure proved more effective at driving change than moral arguments alone, as brands recognized that inclusive representation was both socially responsible and economically advantageous. The business case for diversity—that diverse marketing appeals to diverse consumers and expands potential markets—accelerated changes that activism had long demanded.

The Role of Modeling Agencies Over Time

Early talent scouting relied on informal networks and chance encounters. Agency founders like John Robert Powers, who established the first modeling agency in 1923, initially recruited from theatrical backgrounds or personal connections. Scouts gradually developed systematic approaches, attending social events, shopping districts, and later schools and shopping malls to identify potential models. The scouting mystique—the fantasy of being discovered—became part of modeling’s cultural mythology, though the reality involved calculated assessment of commercial potential based on contemporary beauty standards and market demand.

Modeling contracts and professional standards evolved to protect both agencies and models as the industry matured. Early models often worked without formal contracts, leading to exploitation and unreliable compensation. By mid-century, reputable agencies established standard contracts specifying commission rates (typically fifteen to twenty percent), payment terms, and professional expectations. Industry organizations developed guidelines addressing working conditions, age restrictions, and ethical conduct. However, enforcement remained inconsistent, and the power imbalance between agencies and models, particularly young or inexperienced ones, created ongoing potential for exploitation.

Global agency networks emerged in the late twentieth century as modeling became an international business. Major agencies established offices or partnerships in fashion capitals worldwide, allowing them to place models in markets across continents. The “mother agency” system developed, where a model’s primary agency in their home country maintained relationships with agencies in other markets, coordinating bookings and ensuring the model received appropriate support while working abroad. These networks increased opportunities for models while concentrating power in agencies capable of managing complex international operations.

Ethical issues and modern regulations have become increasingly prominent as awareness of industry problems grew. Concerns about models’ working conditions, exploitation of young models, eating disorders, sexual harassment, and racial discrimination prompted calls for reform. France, Israel, and other countries enacted laws requiring models to provide medical certificates proving healthy body mass index, banning excessively thin models from runways and advertisements. Some jurisdictions restricted working hours for underage models and required chaperones. The #MeToo movement exposed widespread sexual misconduct in fashion, prompting agencies and brands to establish clearer policies and accountability mechanisms, though implementation and enforcement remain uneven.

Technology & the Future of Fashion Modeling

Virtual models and AI-generated influencers represent a controversial frontier in fashion modeling. Computer-generated models like Shudu and Lil Miquela have appeared in campaigns for major brands, offering perfect, endlessly customizable aesthetics without the complications of working with human models. These virtual influencers maintain social media presences with millions of followers, blurring lines between reality and simulation. Proponents argue they offer creative freedom and eliminate logistical challenges, while critics worry they set impossible beauty standards, eliminate jobs for human models, and allow brands to avoid genuine commitment to diversity by creating algorithmically diverse representations without supporting real people from marginalized communities.

Digital fashion and metaverse modeling are emerging as models begin working in purely virtual spaces. As fashion houses create digital clothing for avatars and virtual worlds, they require models to showcase these garments in digital environments. Models have been scanned and transformed into avatars for video games, virtual fashion shows, and metaverse platforms. This digital modeling exists in parallel to physical modeling, creating new opportunities while raising questions about intellectual property (who owns a model’s digital likeness?), compensation (how should models be paid for digital appearances?), and the future relationship between physical and digital fashion presentation.

Sustainability and ethical fashion concerns are influencing modeling practices as the industry confronts its environmental and social impact. Some agencies and models advocate for sustainable fashion, refusing to work with brands that fail to meet ethical production standards. The sample size debate intersects with sustainability, as standard sample sizes that fit only extremely thin models contribute to body image issues and exclude most people from aspirational fashion. Models increasingly use their platforms to advocate for environmental responsibility, transparent supply chains, and ethical labor practices, positioning themselves as conscious participants in fashion’s evolution rather than mere clothes hangers.

The next generation of models may look radically different from current norms, shaped by technological innovation, cultural evolution, and market forces. We might see greater normalization of diverse body types, ages, and abilities as beauty standards continue fragmenting and individualizing. Virtual and human models may coexist, each serving different purposes within fashion marketing. Models might increasingly be multi-hyphenate creators—modeling, designing, influencing, and building businesses simultaneously. The democratization enabled by social media could continue, further disrupting traditional agency gatekeeping. Alternatively, technology might concentrate power in new ways, with algorithms and AI shaping casting decisions and virtual models partially replacing human ones. The future remains uncertain but will likely involve negotiation between commercial pressures, technological capabilities, and cultural values regarding representation and beauty.

How Fashion Modeling Reflects Society

Modeling functions as a mirror of cultural values, revealing what societies prioritize, celebrate, and desire at particular moments. The corseted silhouettes of the late 1800s reflected Victorian values of female constraint and propriety. The boyish flappers of the 1920s embodied women’s liberation and modernity. The glamorous sophistication of 1950s models represented post-war affluence and return to traditional femininity. The waif models of the 1990s coincided with heroin chic and grunge culture. Each era’s dominant aesthetic makes visible the often unspoken values and anxieties animating that time.

Beauty trends frequently interact with social movements in complex, sometimes contradictory ways. The women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s challenged beauty standards as oppressive, yet fashion responded by making models younger and thinner, arguably intensifying pressure on women’s appearance. The body positivity movement of the 2010s challenged thin-ideal beauty standards, leading to increased size diversity in modeling, but critics note this inclusivity often remains superficial, with plus-size models still representing a small percentage of fashion imagery and confined to specific brands. Social movements create pressure for change, but the fashion industry’s response often involves co-opting the aesthetics of resistance while maintaining underlying power structures.

Fashion modeling operates as storytelling, creating narratives that extend beyond the clothes themselves. Editorial fashion shoots construct entire worlds—mysterious, romantic, rebellious, futuristic—with models as protagonists in visual tales. Runway shows frame seasonal collections within thematic concepts, and models embody the characters or attitudes designers envision. Brand campaigns position products within lifestyle narratives, with models representing the aspirational identity consumers might assume by purchasing. This narrative dimension explains modeling’s enduring power: it doesn’t just show clothes but tells stories about who we might become, what beauty means, and how fashion can transform identity.

The evolution of modeling reveals how beauty is culturally constructed rather than objectively determined. Standards that seem natural and inevitable in one era become dated or even bizarre in another. The dramatic shifts in body ideals over the past century—from full figures to boyish slimness to athletic curves to diverse body types—demonstrate beauty’s plasticity. Modeling history documents these changes, showing how social, economic, and cultural forces shape aesthetic preferences. Understanding this history can foster critical distance from current beauty standards, revealing them as temporary cultural constructions rather than permanent truths.

Conclusion: The Evolution Continues

The history of fashion modeling traces a remarkable transformation from anonymous mannequins in nineteenth-century Parisian salons to globally recognized supermodels and digital influencers. Key shifts mark this journey: the professionalization of modeling in the early 1900s, the rise of models as personalities rather than anonymous clothes hangers in the mid-twentieth century, the supermodel phenomenon of the 1980s and 1990s, and the social media revolution that democratized yet complicated modeling in the twenty-first century. Throughout, modeling evolved from a marginal commercial practice into a significant cultural force that shapes and reflects beauty ideals, social values, and aspirations across the globe.

Understanding modeling history matters today because it illuminates the forces shaping contemporary beauty culture. When we recognize that current standards are products of specific historical moments rather than timeless truths, we gain critical perspective on the images surrounding us. History reveals that change is possible—that the industry has transformed before and can transform again. It shows how models themselves, along with consumers, activists, and industry insiders, have driven progress toward greater inclusion and ethical practices. This historical awareness empowers both those within the industry and those influenced by it to question, critique, and imagine alternatives to current norms.

The future of fashion modeling in a changing world remains open, shaped by technology, cultural evolution, market forces, and human choices. We stand at a moment of significant transformation, with AI and virtual models introducing possibilities both exciting and unsettling, social movements demanding authentic inclusion rather than token representation, and new platforms continuously disrupting traditional pathways to modeling success. The next chapter of modeling history is being written now, by models building personal brands on social media, by consumers demanding ethical practices and diverse representation, by designers experimenting with new forms of fashion presentation, and by technological innovations that challenge our understanding of what modeling can be.

As this evolution continues, fashion modeling will likely remain what it has always been: a fascinating, contested, revealing space where beauty, commerce, identity, and aspiration intersect. The clothes may change, the platforms may evolve, and the faces may diversify, but modeling’s essential function—to embody fashion’s possibilities and reflect culture’s values—will endure. Understanding its history helps us approach its future with both critical awareness and hopeful imagination, recognizing both the industry’s persistent problems and its potential for meaningful change.

Leave a Reply